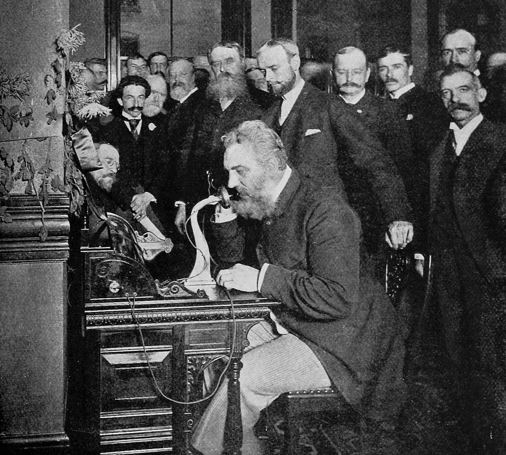

Alexander Graham Bell, 1892. First Telephone Call Chicago-New York

Alexander Graham Bell, 1892. First Telephone Call Chicago-New York

Introduction

Human intelligence involves gathering, formulating, modifying, and applying knowledge, typically in the form of ideas, images, sensations, patterns of response and sense making. We define this process with words like learning, problem solving, planning, visioning, intuition, understanding, creativity, etc. Anyone seeking to generate more effective groups, organizations, institutions and communities learns that individual intelligence is an insufficient factor to successfully handle these tasks. We need to explore collective intelligence and how it can address the unprecedented challenges of the 21st century. The global scale, interconnectedness and the potential impact of those challenges make such exploration more than just a matter of convenience and competitiveness. It is a matter of collective survival and a potential evolutionary leap.

Origins of Collective Intelligence

Primal forms of collective intelligence manifest themselves in the synergies and resilience of ecosystems, which ‘learn from experience’ through the interactive create‐and-test dynamics of evolution. Collective intelligence is more obvious in groups of social animals like ants, bees, certain fishes and birds, and many mammals, including wolves and primates. Members of the first human groups shared the instinct to combine their respective information and expertise to meet survival tasks they could not possibly meet individually. Those early forms of collective intelligence gave rise to language and tools which, in turn, enabled new forms of collective intelligence that could absorb more existential complexity. In today’s world, collective intelligence serves diverse functions, comes in diverse forms, and has many diverse names. For example, there is statistical collective intelligence, also known as the ‘wisdom of crowds’. Although the value that is created tends to be social in origin, it has far-reaching economic implications for business and nations. Online communities are often rich sources of innovative ideas. However, because of their decentralized value-creation, they are capable of diffusing rapidly and disrupting entrenched institutions and societal practices. Like the ‘g’ factor for general individual intelligence, a new scientific understanding of collective intelligence aims to extract a general collective intelligence factor ‘c’ for groups indicating a group’s ability to perform a wide range of tasks.

Prerequisites for Collective Intelligence

Collective intelligence can be triggered through mass collaboration. For this to happen, four principles need to exist:

Openness: Sharing ideas and intellectual property; although these resources provide a potential edge over competitors, more benefits accrue when allowing others to share ideas, gaining significant improvement through collaboration.

Peering: Disclosing product and service developments where users are free to modify and develop it if they make it available for others. Peering succeeds because it encourages self-organization – a style of production that works more effectively than hierarchical management for certain tasks.

Managed Sharing: Companies share ideas while maintaining some degree of control over others like critical patent rights, for example. Limiting all intellectual property shuts out opportunities, while sharing some expands markets and brings out products faster.

Communication: While value generation remains local, internet communication provides access to the best resources and talents globally for solving specific problems collectively at optimal costs.

Benefits from Applying Collective Intelligence

Research performed by Tapscott (University of Toronto) and Williams (London School of Economics) has provided a few examples of the benefits of applying collective intelligence to corporations:

Talent utilization: At the rate at which technology is changing, no enterprise can fully keep up with the innovations needed to compete. Instead, smart firms are drawing on the power of mass collaboration to involve participation of the people they could not employ.

Demand creation: Firms can create a new market for complementary goods by engaging open-source communities. They are able to expand into new fields that they previously would not have been able to without the addition of resources and collaboration from the community.

Costs reduction: Mass collaboration can help to reduce costs dramatically. Firms can release services or products to be evaluated or debugged by online communities. New ideas can be generated by creating opportunities for low-cost R&D outside the confines of the company.

Open-source software: Computing becomes a utility service, and generic open-source software provides a set of services that are assembled appropriately and modified to meet a specific application requirement, generating licensing income.

How to create and maintain Collective Intelligence

According to Thomas Malone, founding Director of the Center for Collective Intelligence at MIT, web-based software tools are enabling people to interact and collaborate in new ways. The Google search engine represents one such innovation. Its PageRank system analyses massive numbers of Web links, created by millions of people, to determine which Web pages are the most popular and thus most likely to be useful. Wikipedia also represents a new system of collective intelligence, said Malone. It has enlisted “thousands of volunteers around the world to collectively create a very large and amazingly high-quality intellectual product, with very little centralized control”. As these examples suggest, the decentralized co-creation of value is not “magical,” said Malone. The first threshold of judgment must be “what are you trying to achieve?” A project that is attempting to brainstorm new ideas will have different design parameters and features than one that is trying to build open source- software or manage a corporate wiki. In short, there is no single approach to online collaboration that can apply to all situations. Malone goes on to extend the idea of assessing group intelligence to include machines as members of human organizations. One basic notion is that group intelligence should be routinely measured and improved. The object of any addition to or rearrangement of a group ought to be improvement in process, flow and intelligence. Malone’s view is that the future of our organizations is one in which people and machines work together, making groups smarter so that they make smarter decisions:

Instead of functional responsibilities, work will be organized by decision-making requirements.

From Collective Intelligence (CI) to Artificial Collective Intelligence (ACI)

While AI continues to progress, the hype is beginning to subside. There is greater realism about the speed of advance in fields like driverless cars, and about just how long human drivers are likely to be needed alongside algorithms. This more nuanced position is also opening important new thoughts on the relationship between AI and collective intelligence: specifically, interest is turning to how AI can help large groups to think together rather than providing an alternative to them. AI can be useful in providing inputs – for example, making predictions about likely patterns of climate change. Moreover, AI can help large groups to deliberate, think and decide more effectively, increasing both the depth and breadth of human collective intelligence. Likewise, AI today is very dependent on people and crowdsourcing. A huge amount of hidden collective labour contributes to ongoing advances in AI. Supervised approaches to machine learning utilise large labelled datasets as their training material. Crowd-work platforms such as Amazon’s ‘Mechanical Turk’ or internet traffic analysis tools such as Google’s ‘reCAPTCHA’, are vital for the ongoing development of AI. This relationship between CI and AI defines Artificial Collective Intelligence (ACI) as a new research area with a few major drivers to start with:

- MIT’s Center for Collective Intelligence (Directed by Thomas Malone) and its Intelligent Collaborative Knowledge Networks (ICKN) to increase knowledge worker productivity and innovation with a three-step process: Innovate, Collaborate, Communicate.

- NESTA foundation, originally funded by a £250 million endowment from the UK National Lottery (CEO Geoff Mulgan), funds and supports projects such as the development of the ‘Collective Intelligence Playbook’ to design and deliver collective intelligence projects.

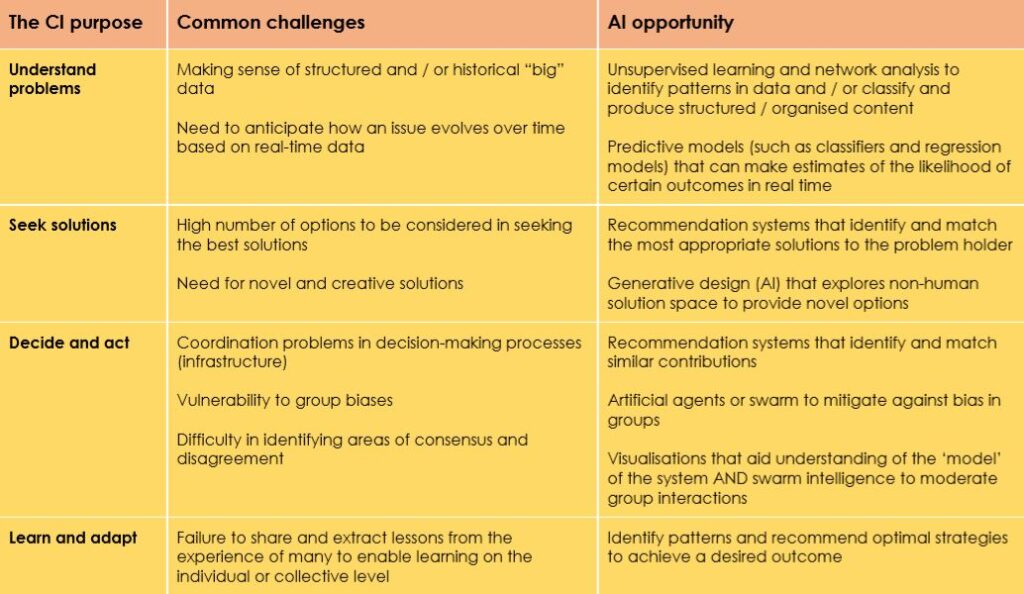

The table below summarises some of NESTA’s research on the correlations between CI’s challenges and how AI might be used to overcome them:

Proposed Guidelines to implement ACI

At present, there is no established framework for understanding and documenting the interaction between AI and CI. So far NESTA’s efforts to map existing practice and academic research have indicated at least four areas in exploring this relationship:

Machines and groups of people taking turns to solve problems together

In this form of interaction people interact with each other and AI, taking turns to solve a problem. This is done either by combining different capabilities of human and machine intelligence or through a system of feedback loops between the crowd and AI to allow for continuous improvement of the system.

People and machines solving tasks together at the same time

Instead of taking turns, this form of collaboration happens in real time where AI and humans both contribute to the same task at the same time. The generative design software for collaborative design developed by Autodesk is one example of this. In this case the AI gives designers and other users real time suggestions for different possible permutations of a solution and design alternatives based on the parameters that it is given.

Enabling better search and matching within a collective

AI can play a vital role in enabling more efficient and streamlined collective intelligence projects by helping people better navigate lots of different kinds of information and tasks. In this type of interaction, AI is used for back-end functionality to improve the experience of individuals via online platforms.

Using CI to audit and support the development of better AI

CI initiatives can be used to support the collaborative or competitive development of AI tools and use crowd contributions to ensure that these tools are better and fairer. Example of this include online activities that focus on AI development to address a challenge such as the ‘Deep Fakes Detection’ competition or the ‘Malmo Collaborative AI’ which is specifically set up as a game to reward the development of more collaborative AI.

Conclusion

The innovations underway to implement ACI are as much social as technological. Although decentralized co-creation springs from deep personal and social impulses, it has proven to be a potent platform for generating valuable information and creative products and services. As such, online communities are highly attractive to businesses seeking to capitalize on new sources of value-creation and to explore how new business models can work with collective intelligence communities in sustainable ways. However, one major issue that must be solved relates to the problem of digital identity. We must create an identity system in which human beings can control their identity. The government will necessarily have to play a role in helping facilitate policies and systems for constructing digital identities in order to establish the trust required to reap the potential benefits of ACI.