Death Island based on a painting by Arnold Böcklin 1890 (Wikipedia)

Death Island based on a painting by Arnold Böcklin 1890 (Wikipedia)

Introduction

The Covid-19 pandemic has caused a major disruption to our individual, social and corporate well-being at an exponential rate. As scientists and researchers race to understand the behaviour of the virus and how to fight it, fear about its devastating potential is growing. While vaccines, possibly available within 6 to12 months, will reduce the life-threatening impact of an infection, the lessons learned will have a lasting impact how we return to ‘normal’. Fighting the outbreak of a virus requires massive data about individuals’ contacts with others plus health information such as body temperature or other symptoms of being infected. For the first time in human history, responding to the outbreak of a pandemic, we have the technical means to collect and analyse this data in real-time to reduce the spread of the virus. Covid-19 is not the last virus to threaten humanity. To be better prepared we need to consider issues such as authority vs. democracy, individual integrity and privacy, augmenting humans with AI as well as ethical issues related to the use of personal data. Above all, however, we need to reflect on emotional issues such as fear, anxiety and panic that go along with the outbreak of a pandemic.

The Characteristics of Fear

Fear is a powerful and primitive human emotion. It can be divided into two responses: Biochemical and Emotional. The biochemical response is universal, while the emotional response is highly individual. Both fear and anxiety are provoked by danger. Fear is the response to a specific and immediate danger. Anxiety results from a non-specific concern or threat. Today many threats are psychological rather than physical, but the same primitive impulse often takes hold. Fear describes a specific and sudden danger to one’s physical well-being. When fear passes, we feel relief and often exhilaration. Our ‘emotional’ brains react immediately to defend against a possible threat. Later we can comprehend the situation more fully with our ‘rational brains’ and decide on the best action to take. With stress about health and fear of losing one’s job, it comes as no surprise that the Covid-19 pandemic is having a significant impact on mental health. Managers of US pharmacies report that prescriptions per week for antidepressants, anti-anxiety and anti-insomnia drugs increased by 21% between February 16 and March 15, peaking the week of March 15 when the virus was deemed a pandemic. The largest increase was in anti-anxiety medications, according to the report, which rose by 34.1% over that month and 18% in the week of March 15.

Fear is a fundamental, deeply wired reaction to protect organisms against perceived threats to their integrity or existence. Psychiatric studies suggest that a major factor in how we experience fear has to do with our emotional state. When our ‘thinking’ brain gives feedback to our ‘emotional’ brain perceiving ourselves as being in a safe condition, we quickly shift from a state of fear to one of enjoyment or excitement. While factors such as context influence the way we experience fear, it is our sense of control that has the biggest impact. When we can recognize what is and what is not a real threat, we are ultimately in a position where we feel to be in control. That perception of control is vital to how we experience and respond to fear. When we overcome the initial ‘fight or flight’ rush, we are left feeling satisfied, reassured of our safety and more confident in our ability to confront and control the things that initially scared us.

Health monitoring: AI’s potential contribution to regain control over fear

There are several existing health-care applications supported by AI, typically extracting health information from large data sets to provide prediction and decision-making support to medical professionals such as radiologists, interpreting fMRI data to detect tumorous cancer cells. Individualized health support is relatively new, with voice recognition technology to detect the potential for heart attacks from speech or to analyse an individual’s cough to detect Covid-19 symptoms. Teletherapy — counselling conducted over video chat or phone — has seen a surge of interest. Many therapists who traditionally held face-to-face appointments are setting up telehealth systems. “Mental health issues as displayed by anxiety, relational problems, alcohol consumption, drug misuse or depression have been amplified through the Covid-19 crisis” states psychiatrist Dr. Anne Gilbert, who runs a virtual healthcare program at Indiana University. As new mobile sensor technology provides information about various physical health parameters such as body temperature, heart rate, skin condition, blood sugar, electrical brain activity (EEG), facial expressions and more to come – all coupled with GPS for user location information – the spectrum of AI-supported telemedicine applications providing health-care is rapidly rising. Besides improving an individual’s health and his/her well-being, the analysis of data collected from thousands of individuals in real-time will provide the means to rapidly detect and respond to pandemic outbreaks. This information improves our perception of control over the pandemic, partially easing our emotional reactions of fear.

The motivation to overcome fear and anxiety

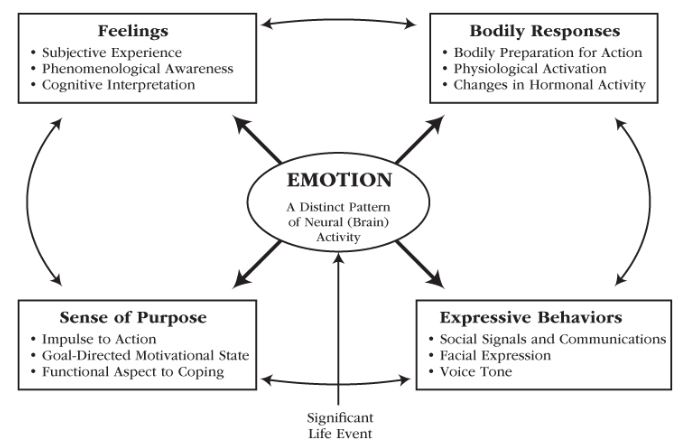

The emotional response to fear is highly personalized. Because fear involves some of the same chemical reactions in our brains that positive emotions like happiness and excitement do, feeling fear under certain circumstances can be seen as fun, like when you watch scary movies. Fears may be a result of bad experiences or trauma or the result of losing control. In our world of exponential change and ever-increasing complexity, our motivation to solve problems is one of our most valuable commodities. Emotions are considered motivational states because they generate bursts of energy that get our attention and cause our reactions to significant events in our lives. Emotions rapidly synchronize four interrelated aspects of experience: feelings, bodily response, sense of purpose and expressive behaviour as depicted by the following graph (Credit: PositivePsychology.com):

The outbreak of a global pandemic such as Covid-19 triggers fear as an emotional state that interacts with the four components described above. The sense-of-purpose component generates an impulse for action to cope with the circumstances at hand. The bodily-response component causes our heart to pump more blood, our respiration to increase, our pupils to dilate to help us see better, our liver to put extra sugar into the bloodstream as we begin to perspire to cool the body. We feel these experiences and they motivate and guide our behaviour and decision making, but most importantly, they have a significant impact on our mental and physical health. As bodily reactions can be individually monitored with sensors in real-time, adding information gained from our emotional response improves our sense of control and motivates us to act responsibly against the paralyzing effects of fear and anxiety caused by a pandemic outbreak.

Who is in Control, what about ethics?

Issuing warnings about a global pandemic triggers state-controlled mechanism that impact our individual, social and corporate lives. While authoritarian states like China have the means in place to react quickly once a pandemic is acknowledged, democratic nations must declare a state of emergency, enforcing ‘authoritarian control’ by reducing ‘parliamentarian control’. Experience with the current pandemic shows that citizens are quite willing to follow government orders such as social isolation or economic closings. The longer this emergency lasts, however, the greater the growing unrest and frustration among the public. Consequently, it is vital to break the pandemic as quickly as possible with AI supported computational resources, monitoring the progress of the pandemic’s curtailment along with rapid drug development based on the data collected. Analysing reactions of individuals across the globe, it appears that health protection counts more than the concerns about data privacy and data protection. Consequently, the question lingers what happens when the pandemic is over. Based on past experiences the public will be suspicious about the claim that all data has been anonymized or destroyed. All ethical discussions that have accompanied the application of AI since years will resurge as the potential misuse of highly personal health information opens the door for cybercrime at an unprecedented rate. This global problem needs a global solution. To discuss issues about ethics requires a legal framework with global acceptance, something that does not exist today.

Conclusion: Lessons learned

There is likely no going back to ‘normal’ once the current Covid-19 pandemic is under control. We have learned that video-enhanced communication can reduce the need to travel to meetings and conferences, positively impacting climate concerns. We have also learned that the process of digital transformation and the introduction of AI supported real-time health-monitoring is accelerating, creating opportunities for new, innovative virtual assistant health-services. Most above all we have learned that the price of battling pandemics is access to our personal data. Raising awareness and understanding of our emotions vis-à-vis the rationality of intelligent machines are fundamental in overcoming fear as presently experienced by the devastating impact of Covid-19. This mindset supports the ongoing trend towards human-level AI, hopefully advancing humanity for the benefit of all.