René Descartes 1649 Picture Credit:Wikipedia

René Descartes 1649 Picture Credit:Wikipedia

Introduction

Western philosophers have struggled for centuries to comprehend the nature of consciousness. Some basic questions include whether consciousness is the same kind of thing as matter; how consciousness relates to language; how consciousness relates to the world of experience and whether it may ever be possible for computing machines to be conscious. ‘Cogito, ergo sum’ is a Latin philosophical proposition by René Descartes usually translated into English as ‘I think, therefore I am’. He formulated the first modern version of mind-body dualism and is considered the father of modern philosophy. With the ongoing advancements in neuroscience and the emergence of neurophilosophy as an academic discipline, consciousness has become a major research topic which challenges Descartes proposition:

stipulating that the human brain and its bodily interactions provide the foundation of human consciousness. According to Patricia Churchland, generally considered the doyenne of neurophilosophy, the human brain is a product of biological evolution, and as we increasingly appreciate, evolution is remarkably conservative. Our brains are very similar in organization, neuronal components, and neurochemicals to the brains of chimpanzees, monkeys, rodents, and even in basic ways, to those of reptiles and fruit flies. However, we cannot expect engineering perfection in the products of evolution. Improvements to a nervous system are not built by starting from scratch but are modifications and extensions of what already exists. If we approach the problems of nervous system function strictly as engineering problems, setting our goals to figure out how a task could in principle be done, we may find a cunning solution that is nothing like what evolution has produced so far.

Consciousness and the shift from Philosophy to Neuroscience

Kathinka Evers, leader of the Neuroethics and Philosophy Group of the EU’s Human Brain Project (HBP), sees consciousness as a continuum. Her work on consciousness comes from traditional analytic philosophy that is also supported by empirical research. She works closely with HBP neuroscientist Jean-Pierre Changeux, recipient of the Albert Einstein World Award of Science in 2018, whose theories on the brain helped shift the idea of the brain as a ‘black box’ that simply processed input-output signals. According to Jean-Pierre and others, the brain is intrinsically and autonomously active: even in the absence of external signals it develops spontaneous representations and evaluates them, striving to build meaningful representations of the world. According to this theory the brain produces and tests so-called pre-representations to see how well they fit – both with previously established presentations and with the external environment in which the brain operates. If there is a good fit it is stabilised as a representation and a model, if it doesn’t fit then it is discarded. Evers says research on consciousness has traditionally focused primarily on awareness, and comparatively less on the activities that are typically labelled ‘unconscious’. However, the latter can be very rich, as recent research in neuroscience and psychology is making increasingly apparent. “Whether consciously aware or unaware, the brain correlates and selects information, associate’s meanings, rapidly performs computations, sophisticated mathematical operations, complex inferences, perceives the affective value of stimuli and influences motivation, value judgment and goal-directed behaviour. In everyday life, we experience the continuum of the different levels of consciousness all the time. For example, when we drive a car, we can do so while carrying on a conversation, pondering a philosophical problem, and listening to music, all at the same time: different levels of consciousness collaborate to, hopefully, keep the car steadily on the road.”

Collaboration between Philosophy and Neuroscience, the emergence of Neurophilosophy

The collaboration between neuroscience and philosophy is relatively new. Only a few decades ago philosophy averted empirical perspectives while neuroscience took little interest in philosophy.

However, within recent decades science has begun to take an interest in consciousness as a subject for serious scientific pursuit. In the earliest stages of the 20th century one had behaviourism which completely discarded and rejected mental terms as improper for scientific study. Then came functionalism in the middle of the century, leaving emotions out in the cold, so in terms of understanding the human mind and its complexity, it was an unsuccessful pursuit as well. It was the combination of neuroscience getting involved in studying consciousness and philosophy becoming more open to studying natural sciences, including neuroscience, that brought about a theoretically more promising environment leading to the emergence of neurophilosophy. Many of the questions raised by modern neuroscience are similar to the ancient philosophical questions such as free will, what it is to be a self, the relation between emotions and cognition, or between emotions and memory. One of the main issues in neurophilosophy is the question of methodology. How can we link empirical data, so-called facts as obtained in neuroscience, to the concepts and their meaning as dealt with in philosophy? How can we infer from neuroscientific data about consciousness to the philosophical concept of consciousness and, vice versa, how can we translate the latter into experimental designs to test it empirically? This neurophilosophical gap needs to be bridged if neurophilosophy is to succeed in the long term.

The Quest for Consciousness

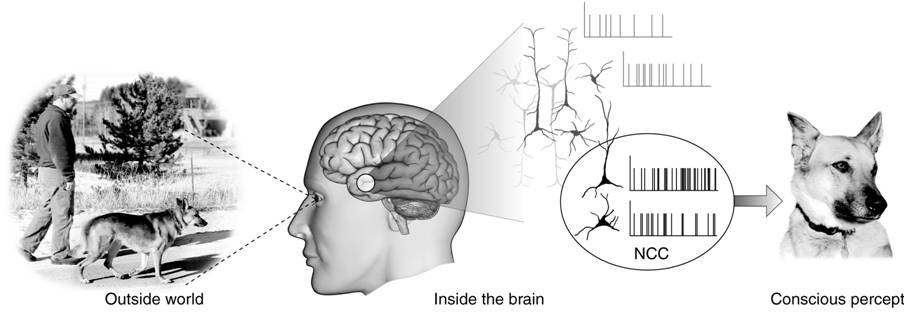

Marcello Massimini, HBP scientist and Professor at the university of Milan believes that we are close to a profound leap in our understanding of consciousness. “We are in a beautiful position, unlike 40 years ago we now know a lot about neurons, we have beautiful insights from neuropsychology, from clinical neuroscience, from quantitative imaging. It is more about putting things together rather than doing more discovery. Of course, in putting things together you might need to do a new experiment, but we don’t need to search for a magic neuron or something special and crazy.” One of the strengths of the HBP is the way it can bring together the different fields of thinking around consciousness and combine these with the power of simulations to address fundamental questions about the relationships between consciousness and the physical world. To Christof Koch, chief scientific officer of the Allen Institute for Brain Science in Seattle, the answer to these questions may lie in the fabric of the universe itself. Consciousness, he believes, is an intrinsic property of matter, just like mass or energy. Organize matter in just the right way, as in the mammalian brain, and voilà, you can feel. We need to identify what he calls the ‘neural correlates of consciousness’ (NCC). The NCC describe the search for those minimally neuronal conditions that are jointly sufficient for any one specific conscious percept that we can experience.

Schema of the neural processes underlying consciousness, from Christof Koch

Schema of the neural processes underlying consciousness, from Christof Koch

Koch, now 62, has spent nearly a quarter of a century trying to explain why, say, the sun feels warm on your face. But after writing three books on consciousness, Koch says researchers are still far from knowing why it occurs, or even agreeing on what it is. But Koch hasn’t given up his search for a grand theory that could explain it all. In fact, he thinks consciousness could be explained by something called “integrated information theory,” which asserts that consciousness is a product of structures, like the brain, that can both store a large amount of information and have a critical density of interconnections between their parts.

Can a Machine have Consciousness?

The question of whether machines can have consciousness is not new, with proponents of strong artificial intelligence (strong AI) and weak AI having exchanged philosophical arguments for decades. To the philosopher John R. Searle machines with strong AI understand cognitive states. In contrast, weak AI assumes that machines do not have consciousness, mind and sentience but only simulate thought and understanding. Whereas, we know about human consciousness from the first-person perspective, artificial consciousness will only be accessible to us from the third-person perspective. Instead of guiding the computer in its learning process it is given the ability to interact with its environment and will then learn from these interactions. This so-called Seed-AI is by design capable of self-instructed learning and best understood by seeing it as the machine equivalent to a human baby. Both begin without any representation of the environment and itself but will then structure their inputs, formulate goals and improve themselves according to their goals and their perception of the world.

In a paper published by the journal ‘Science’ in October 2017, neuroscientists Stanislas Dehaene and colleagues make the case that consciousness is ‘computational’ and subsequently possible in machines. “Centuries of philosophical dualism have led us to consider consciousness as irreducible to physical interactions,” the researchers state. The empirical evidence of the study suggests that consciousness arises from nothing more than specific computations. In their study the scientists define consciousness as the combination of two different ways the brain processes information:

- Selecting information and making it available for computation, and

- the self-monitoring of these computations to give a subjective sense of certainty—in other words, self-awareness.

The computational requirements for consciousness, outlined by the neuroscientists, could be coded into computers. “We have reviewed the psychological and neural science of unconscious and conscious computations and outlined how they may inspire novel machine architectures. The most powerful artificial intelligence algorithms remain distinctly un-self-aware, but developments towards conscious thought processing are already happening.” If such progress continues to be made, the researchers conclude that a machine would behave as though it were conscious.

Conclusion

Assuming this is correct, then neurophilosophy must be engaged to deal with the ethical issues of conscious machines. These machines are designed to solve specific problems. The vast capability of humans to associate and self-reflect across all facets of world-knowledge will differentiate human consciousness from machine consciousness. Combining both, to generate value in a societal context, represents a major challenge human must resolve within the coming decades. Well known Neuroscientist Henry Markram, Professor at the EPFL in Lausanne and founder and director of the Blue Brain Project makes the point, that theories about consciousness need to be verified by disproving the theory. In a coffee-brake discussion we had during the kick-off meeting of Switzerland’s new ‘Cognitive Valley’ AI-initiative a few days ago, we discussed the falsification theory of Sir Carl Popper, one of the 20th century’s most influential thinkers. “It is easy to come up with a theory about consciousness, to disprove it is much harder. So far, we have not reached this point”, Prof. Markram remarked.